If I didn’t know that my last post would open a can of worms, I should have! In this instance, though, I am quite glad that it did. I realized that I had a lot of misunderstandings and was making a lot of unfair assumptions. Thank you to everyone that has been helping me learn through Tweets, private messages, emails, and texts! In particular, thank you to Thomas Sauer for your ACTFL expertise, Sara-Elizabeth Cottrell and Justin Slocum Bailey for your knowledge of SLA research and passion for making it accessible to teachers, Amy Lenord and Lisa Shepard for your passion for "proficiency" (whatever we mean by that, ha!) and desire for language educators to work together toward our common goals, and Mira Canion for knowing me well enough to give me frank advice. Many others have joined in the conversation here and there, but these folks are the ones whose phones have been exploding for three days straight with Twitter notifications.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THE CAN-DO STATEMENTS?

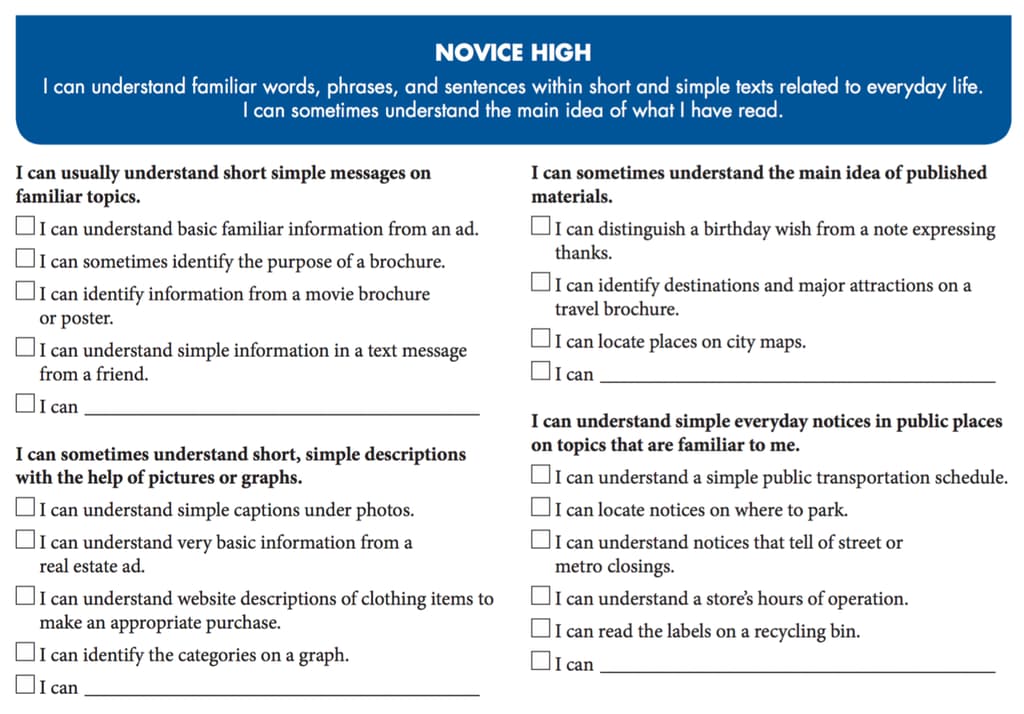

The biggest misunderstanding that I had was that the Can-Do Statements are examples. I don’t believe that I am alone in this misunderstanding, and that was a major part of the frustration that sparked the thinking behind my last blog post. Teachers are being asked to align their curriculum with Can-Do Statements, when what should be asked of us—if schools are using the Can-Do Statements in the way that ACTFL intended—is that teachers write their own Can-Do statements. This is in line with the principles of backward design; that we should set a goal before we begin, and that goal should inform the journey. The key point for me, though, is that teachers should set their own goals for their students: goals that are communicative (interpretive, presentational, and/or interpersonal) and informed by an awareness of language acquisition. Let’s look at this chunk of Can-Do Statements from Interpretive Reading/Novice High (Page 37):

At the top, you see a general “I Can” statement for a Novice High language user with respect to Interpretive Reading. It is very general. Now, look at the statements listed below it: we’ve got bold “I can” statements with more detailed ones below them and a blank space. I used to think that the blank space was for us to write in additional statements. Not so! You may certainly use the statements above the line, but you might choose to ignore them and write your own, unique learning target for your students on that line, discarding the rest. You might not even tackle any I Can statements in that category! ACTFL has put together these pages and pages of statements for you to have many statements that might work for your students and to have many statements after which to model your own. The possibilities are endless! So if your department chair or program director asks you something like, “Show me which of ACTFL’s Can-Do Statements your students are working on right now”, take that opportunity to have a conversation about the goals that you have set for your students, why you chose those goals, and how they are modeled after the kinds of goals that ACTFL has laid out as possibilities in this very thorough document. And be very gracious, of course, because I wouldn't be surprised if you are just learning this yourself, much like I learned this over the last few days! Thank you very much to Mira Canion and Thomas Sauer for helping me to identify and fill the hole in this misunderstanding. Also, it is certainly possible that I do not yet have a perfect understanding of ACTFL’s intended use of the Can-Do statements, so please continue the conversation with me in the comments and on Twitter!

A concern that I have about the Can-Do statements is that they are—I believe they are, anyway—aligned with ACTFL’s Proficiency Guidelines. One very interesting part of the Twitter conversation has been what does proficiency mean?

The ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines are a description of what individuals can do with language in terms of speaking, writing, listening, and reading in real-world situations in a spontaneous and non-rehearsed context. […] These Guidelines present the levels of proficiency as ranges, and describe what an individual can and cannot do with language at each level, regardless of where, when, or how the language was acquired. […] The direct application of the ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines is for the evaluation of functional language ability. The Guidelines are intended to be used for global assessment in academic and workplace settings. However, the Guidelines do have instructional implications. - See more at: http://www.actfl.org/publications/guidelines-and-manuals/actfl-proficiency-guidelines-2012#sthash.a0bEPrON.dpuf

Did you catch that? The Proficiency Guidelines have instructional implications but their function is in the ‘real world’! In a classroom setting, we cannot assess “proficiency” because we can only at best simulate real world scenarios; and the simulation will never be the same as the real deal. Instead, we must look at the guidelines and say, “Yes! THAT is how I want my students to be able to communicate in the real world!” and then plan instruction accordingly, informed by SLA research as to what practices result in language proficiency. The Proficiency Guidelines remind us to keep the end in sight: to remember that communication (in ALL modes, individually and collectively) is the goal. Don’t get caught up in accuracy; in memorizing vocab lists and conjugating verbs. Remember that we want to train up a generation of language students that are able to use the language and have the tools at their disposal to use it better tomorrow than they did today. That being said, the alignment of the example Can-Do Statements with the Proficiency Guidelines causes some concern for me. Click here to read Justin's insights about the Can-Do Statements, and keep reading for more of mine.

PERFORMANCE OR PROFICIENCY?

Another big misunderstanding that I identified through this conversation is that I usually mean “Performance” when I say “Proficiency”. I’m not ever measuring my students’ linguistic proficiency (as defined above); I am only measuring—can only measure—their performance in the classroom context. In addition to the ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines, there is a separate document called the “ACTFL Performance Descriptors for Language Learners”, which I previously thought were somewhat interchangeable with the Guidelines, or perhaps redundant, or most honestly I didn’t really think about their relationship at all. These Performance Descriptors are what I used to create the rubrics that I use for my assessments, but I never really spent time digging into where they came from or what they mean. How silly is that?! To be honest, I feel awfully foolish. See Page 6 of the Performance Descriptors document to read ACTFL’s comparison of Performance vs. Proficiency!

SOME CONCERNS

But if the Proficiency Guidelines are real-world descriptors of communication outside the classroom context, why are the example Can-Do statements derived from them? By modeling the example Can-Do Statements after the Proficiency Guidelines, which are real-world descriptors of communication outside the classroom context, teachers are encouraged to design assessments that simulate real world interactions (hence, the IPA). In order for students to be successful on those assessments, we must prepare them. And what is preparation, but practice?

While we know that output comes from input, and so in theory we could just stuff students full of comprehensible input and then, on the day of the IPA, the output would just flow out of them, I think we are insightful enough to realize that that’s not what teachers will do. If students have to complete an interpersonal or presentation component of an IPA, then teachers will build practice opportunities into their instruction. This is NOT a bad thing; it’s a good thing! However, we must keep in mind the proportion. If an IPA is equal parts interpretive/presentational/interpersonal, we might be tempted to spend equal amounts of class time practicing those modes of communication. However, SLA research would not support that instructional model. Output comes from Input. I believe that THIS is the major point of departure between so-called “camps” of proficiency minded language teachers: just how much comprehensible input is needed before practicing output, and just how much output (interpersonal and presentational) practice should happen in class. You see, we all believe the same things—we know that language is acquired through comprehensible input, that instruction, therefore, must be in the target language and comprehensible to students, and that proficiency is the ultimate goal. The way in which those beliefs manifest themselves in instruction will be different with each teacher, even among teachers that would say that they teach “the same way”. We are all producing students that are more proficient; better equipped than the students in our generation of learners, so we are all seeing great outcomes. I’m won’t say that I think that it doesn’t matter how much input you provide or how much practice you facilitate, because I think that it very much does. And while you might be seeing great outcomes, who’s to say that you wouldn’t see even BETTER outcomes if you didn’t play with the percentages a bit? As someone who incrementally transitioned from much output (cooperative learning, baby!) to much input, I can say from my experience that the amount of comprehensible input matters. The more comprehensible input that you provide for your students, the less output practice you will need. (It’s also important to note that all modes of communication are usually happening while the teacher provides comprensible input; interpretive is simply the most significant.)

Similarly, why does the Interpretive section of the Performance Descriptors describe interpretation of AUTHENTIC texts only? They do not provide a way to measure progress in interpretation of non-authentic texts. For this reason, teachers are subtly encouraged to use only authentic texts in class. I don’t believe that interaction with authentic texts is the best way to improve interpretation of authentic texts, and I don’t believe that SLA research would support that. In my experience, students are best able to interpret authentic texts through interaction with non-authentic texts, texts that are created to provide a strategic scaffolding that prepares the learner to interpret authentic texts.

Both of these concerns were affirmed by a teacher that shared their thoughts on this whole conversation in a private message. This particular teacher considers themselves to be a “text-based teacher” (as I defined it in my last post) in a “task-based” department. I’m sharing this excerpt here anonymously with the teacher’s permission:

The biggest difference that I see [between text-based teaching and task-based teaching] is when crafting a task-based assessment, typically an IPA, there is always an element of performance (whether it is presentational or interpersonal) that the students are expected to produce. At the novice levels this requires a great deal of time to practice or rehearse. Students might have to present about their family members, or have a conversation about their daily routine. From my point of view, this practice time, which might take many forms but always involves students speaking and putting out language, takes a lot of time away from the CI that I could be providing them. From my experience, task-based assessment requires lots of output. For me, a text-based assessment focuses overwhelmingly on comprehension rather than production.

The second difference would be in the insistence on "authentic" resources. Again, from my experience, the tasks are nearly always based on "authres" to make them more realistic. Thus, the students listen to native speakers talk about their days, or read infographics about families, or use maps of cities in the target cultures to locate places. Even as a text-based teacher I would use some of these resources (though I wouldn't denominate them as any more authentic), but I would use more texts (i.e. stories and novels) specifically intended for students in general or for my students in particular. More often than not I find those texts to be a) more comprehensible to my students (less scaffolding, glossing, etc... needed) b) more compelling and c) linguistically much more rich.

MORE CONVERSATION NEEDED

I guess that, in sum, I don’t know what I don’t know. I thought that I knew a lot of things about the resources that ACTFL has put together for curriculum planning, but in reality I knew a lot of things and had (still have, I am sure) a lot of misunderstandings. I look forward to continuing this conversation and studying the resources and the research further. I want to make sure that my curricula provide instruction that results in the best outcomes possible, and I want to be able be able to talk about how our profession can do better by our students. For the former, I need continue to learn more about Second Language Acquisition. Aside from just reading, reading, reading, two great, teacher-friendly resources are the Black Box Podcast and Tea With BVP. I’m also excited to learn from both Stephen Krashen AND Bill VanPatten this summer at iFLT in Chattanooga. For the latter, I need to make sure that I understand how ACTFL intends for us to use the resources that it has developed. I also need to make sure that my colleagues and I have a common understanding of the terms that we are tossing around in our conversations. It seems that most of the time—but not always—we agree but sound like we don’t because we have different understandings of some key terms, like “proficiency”, “task”, “performance”, “comprehensible”, and “practice”. As Mira pointed out to me, it is also most helpful for me to describe what I do and let other people describe what they do; not to assume I know what they are doing in their classrooms without giving them the chance to explain for themselves.

Anyway, I’ve spent long enough on this post. Keep the conversation going, and keep being kind! It is so fun to think through these things when everyone is kind and respectful, even in (apparent) disagreement.

As always, I reserve the right to be wrong ;-) Let's see what the next round of conversation reveals!