Note to the reader: This post talks about a popular party game that has long been called "Mafia", although I no longer advocate for calling it by that name. Mafia is a term that refers to crime organizations that are often associated with specific countries and cultures; most notably, Italian, Russian, Japanese, and Irish. In the same way that we do not want to glorify so-called drug ‘lords’ that have destroyed lives in Spanish-speaking cultures and beyond, we also do not want to glorify organized crime in any culture. Teachers have created many different versions of this game, including non-violent versions, and so I will refer to the collective versions of the kind of game popularly known as Mafia as 'Elimination".

The Elimination Game is not new to language classrooms.

Language teachers have been using Elimination in their classrooms—just like I was—for years (I recently stumbled across an old post of MICHELE WHALEY'S from 2011 about the game--of course Michele had already blogged about it!). Elimination (a.k.a. Mafia) is a fun party game in which many of us saw potential for language acquisition. It didn’t occur to me to blog about it until…oh…five years into my blogger life, just like many other teachers have been using this game quietly for years without shouting it from the rooftops.

Share what you're doing!

When we share our ideas—whether it be on a blog, in a Facebook group, in a presentation to a local group, or while out to dinner with friends at a national conference—that idea goes out into the universe, and those ideas grow and become better. Those ideas do more than we could ever imagine and become better than we had conceived ourselves. That is precisely what has happened since I sent this idea out into the universe in 2015, and I couldn't be happier.

So let me tell you about Elimination (historically known as Mafia).

The time we played Elimination at iFLT

Two nights ago, we had a little Elimination party at iFLT. It was short because Starbucks closed earlier than we thought, and Game-Master Greg Gross did a fantastic job narrating the game in English and weaving in pop-up adaptations for the language classroom as we played. It was a huge group of people, so I am glad that he took on the responsibility of moving the game along and keeping track of all of the events of the game.

Well, Diane Neubauer and Pamela Rose told me that Ben Wang, who is a teacher at Vermont Commons School in South Burlington, had adapted and simplified the game so that it could be played with beginning Mandarin students. He was going to demonstrate it for a group of Chinese teachers, and they were looking for some non-Mandarin speakers to participate. I totally would have played, of course, but I don’t know any Mandarin. “That’s okay”, Ben said, “You can play”. Knowing how Elimination works, I was like, “Oh, no, I mean I really don’t know any Mandarin”. So Pamela and Diane insisted that he had simplified it and I really could play. Yeah right, I thought!

Ben Wang, Mandarin Elimination Master, demonstrating the gesture for "Assassin" (in Mandarin, the word literally means "the hand that kills")

Ben Wang, Mandarin Elimination Master, demonstrating the gesture for "Assassin" (in Mandarin, the word literally means "the hand that kills")

Oh. My. Word. Guys, Ben Wang is a friggin' genius. Ben Wang’s Elimination? It’s…it’s…it’s…it’s everything that Elimination in a world language class should always have been and I am in awe of how he transformed it!

Keep reading to learn how to play Ben Wang Elimination. (It’s way better for language learners. WAY better.)

At the end of the post, read about two non-violent versions of the game.

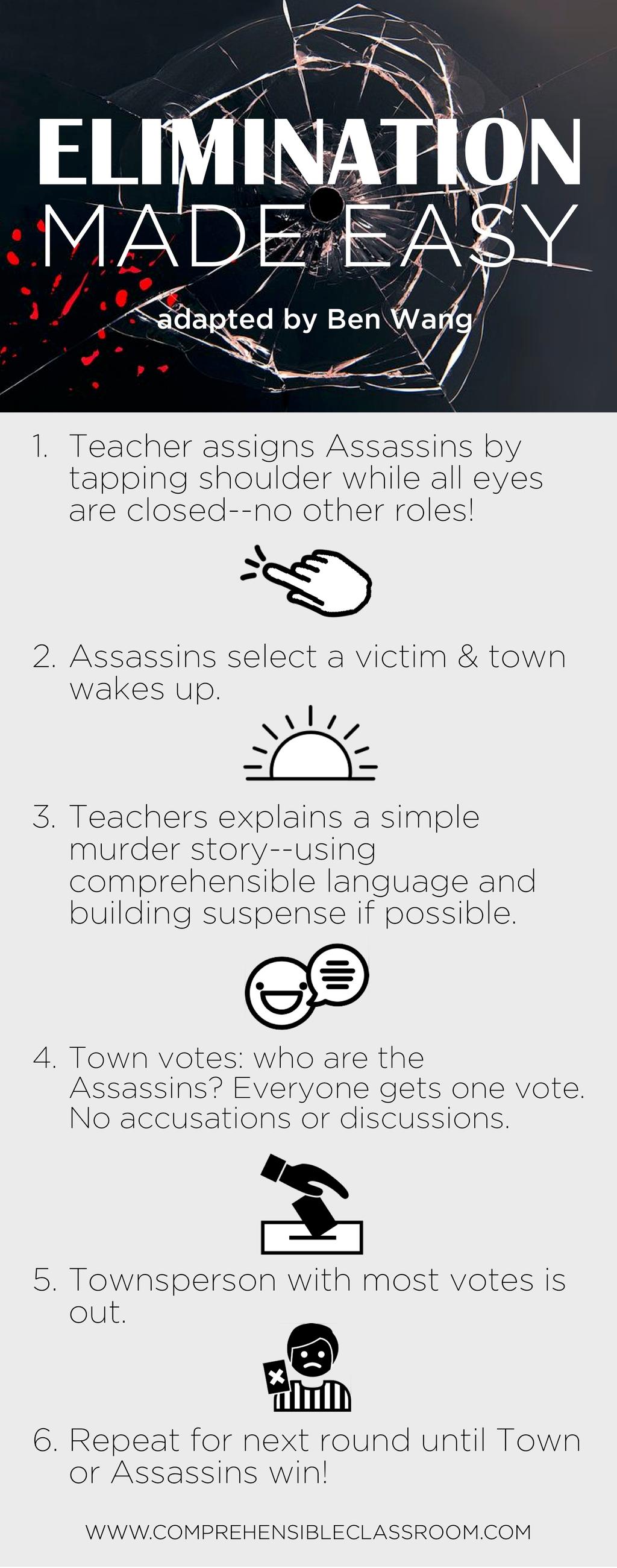

HOW TO SET UP SIMPLIFIED ELIMINATION:

With limited time to play, unsure of when we would be kicked out of the space that we were using without renting it (yikes!), Ben quickly established meaning by telling us some the Mandarin words and showing gestures for “he/she”, “kills”, “dead”, “assassin”, “townspeople”, “sleeps”, and “wakes up”. Ben says that before he plays for the first time with his students, he does a MovieTalk activity with the trailer from the movie Insurgent, being certain to target the words that he introduced to us, in addition to the other words that he would bring into the game as it played out (goes, is there, wants, eats, sees).

Ben used a few tricks to support comprehension once meaning had been established, including the use of gestures and assigning a particular student the responsibility of making a sound each time that Ben said a particular word. (For example, when he said the word for “who”, Cathy Scurlock [a Spanish teacher from Nebraska] had to say “Hoo-hoo”, like an owl.) These simple tricks did much to support our comprehension.

ELIMINATION SIMPLIFICATION #1: Role assignment

Instead of using playing cards, Ben assigns the roles by having everyone in the class close their eyes. With everyone’s eyes closed, he walks around the outside of the circle and says as he passes each person, “Is s/he the killer?” Is s/he the killer?” As he was walking around the room, he chose the assassins and tapped them on the head (there were four in our large game). This was brilliant, because it gave us so many repetitions of that phrase!

ELIMINATION SIMPLIFICATION #2: Limited roles

No police officers or doctors were assigned. Each participant was either a townsperson or a killer.

Ben has participants act out the events leading up to their deaths as he builds suspense

Ben has participants act out the events leading up to their deaths as he builds suspense

ELIMINATION SIMPLIFICATION #3: Delayed death announcement

Most narrators reveal the murder victim fairly quickly after the townspeople wake up from the night of terror and save the creativity and suspense for building the story about how the victim died. However, Ben focused all of his creative energy on building suspense as we waited to find out which participant had been killed. He brought different participants into the murder story, and it wasn’t until the very end that we would know which one had actually become the victim. See some examples under Adaptation #4. This strategy was so effective in drawing us into the game, I can’t even tell you. I mean, I loved Mafia before, but this was awesome. As Ben narrated, you were hoping and hoping that he wouldn’t say his name, and wondering whose name he would say next. And if he did say your name, you were hoping that you wouldn’t be the person that actually ended up dead! He worked many twists and turns into the stories, even with simple language, so we were always on the edge of our seats. By building suspense here, he was able to make Adaptation #6. As Diane Neubauer shared in our post-Mafia debrief, she thinks it’s brilliant that he used this suspenseful misdirection because he sometimes made the mafia a memorable part of scene, as one of the people that didn’t end up being killed, and it serves the purpose of further puzzling the participants because we surely “know” that it couldn’t have been so-and-so because they were eating pizza!

ELIMINATION SIMPLIFICATION #4: Similar murders

I want to smack myself on the forehead for not thinking of this one, “DUH!” In TPRS®, the same basic series of events often repeats itself several times at different locations or with different people, each time only slightly differently, before finally resolving. We do this in order to get in many repetitions of the same, limited number of target structures. Ben turned Mafia into a TPRS® story of sorts—the only difference was that he did not ask for student input (although he certainly could have). He was storyTELLing, not storyASKing. And boy oh boy, did I love it. Some of the stories that he told were:

Louisa wants a hamburger. She goes to McDonalds. She is at McDonalds. She eats a hamburger. She eats two hamburgers. She eats three hamburgers. She eats four hamburgers. She eats five hamburgers. Louisa is not good (meaning that she doesn’t feel good). She goes to the dumpster. She sees Pamela at the dumpster. Pamela is dead.

Linda wants pizza. Martina wants a hamburger. Linda is at McDonalds. Martina is at Pizza Hut. Linda goes to Pizza Hut. Martina goes to McDonalds. Martina eats a hamburger. She eats two hamburgers. She eats three hamburgers. She eats four hamburgers. She eats five hamburgers. Linda eats pizza. Martina is dead. Martina ate a hamburger with poison.

Anne Marie, Sam, and Cathy fell victim to an assassin in a Mac Truck--Keith Toda (Todally Comprehensible Latin) and Julie Thompson look on.

Anne Marie, Sam, and Cathy fell victim to an assassin in a Mac Truck--Keith Toda (Todally Comprehensible Latin) and Julie Thompson look on.

Cathy wants a hamburger. Anne Marie wants a hamburger. Sam wants a hamburger. They are not at McDonalds. They see McDonalds. They want to go to McDonalds. There is an Interstate. They go to McDonalds. They see a Mac Truck. The assassin is in the Mac Truck. They are on the Interstate. The Mac Truck kills them. They are dead.

Diane wants a hamburger. She goes to McDonalds. She eats a hamburger. She eats two hamburgers. She eats three hamburgers. She eats four hamburgers. She eats five hamburgers. She is not good. She goes to the dumpster. She sees Louisa. Louisa is at the dumpster. Louisa is not good. A ninja assassin kills them. Louisa is dead. Cathy is dead.

ELIMINATION SIMPLIFICATION #5: Multiple murders

To make the game move more quickly in large groups, the assassins could be instructed to kill more than one person on any given night. This isn’t necessarily Ben’s adaptation, but since I never said it before on the blog, I am saying it now.

ELIMINATION SIMPLIFICATION #6: Voting without discussion

Once Ben finally finished describing/announcing the death, he would ask, “Who is the assassin?” Then, he walked around the circle to each person that was still in the game and asked, “Is [name] the assassin?”. The rest of the living participants voted (they could only vote once). The accused assassin held up the number of fingers that represented the number of votes that they received. So if five living participants thought that Dr. Krashen was the assassin, Dr. Krashen had to hold up five fingers. Ben went all the way around the circle, repeating the question. “Is [Jeff] the assassin?” (Vote). “Is [Julie] the assassin]?” In this very beginning version of Mafia, the participants did not have an opportunity to defend themselves (although that could certainly be added as students’ language ability improves). The person with the most accusations was out.

ELIMINATION SIMPLIFICATION #7: Revenge

The person that received the most accusations was pitchforked by the townspeople, since Ben’s gesture for townspeople was a pitchforking motion. Ben said, “Townspeople! Kill [accused assassin]!”

ELIMINATION SIMPLIFICATION #8: Post-death revelation

Once the assassin had been pitchforked, Ben asked the ghost of the assassin, “[Name], were you an assassin?” And the assassin revealed whether or not he or she really was one of the assassins. This was super dramatic and suspenseful, and it motivated us to get to the next round!

ELIMINATION SIMPLIFICATION #9: Let there be ghosts

Although I have been playing Mafia on my own for years, and using it in Spanish classes for years, I had never once played as a language learner. This experience was invaluable to me, and it affirmed to me the importance of Terry Waltz’s exhortation to always be a novice in some language. It is important that we never forget what it feels like to be a language baby, and to have insights into what our students need from us as we experience a language lesson from their perspective. Once my students were eliminated from the game, I always made them watch, silently. This was never an issue, because it is just as—if not more—compelling to watch the game being played when you know everyone’s true identities. However, I realized when I was playing in Mandarin that I needed to have the freedom to engage with and respond to Ben, the narrator. I needed to be able to answer the questions that he asked and to participate fully in the game in order to process the language with which he was flooding me. I realized this very quickly after being killed off, and so I requested and Ben permitted me to continue playing the game as long as I continued to “go to sleep” each night and not discover the true identities of the killers. I participated as a “ghost”. I didn’t have a vote, but other than that, I could participate fully. I wanted to stay in the circle in order to be part of the action. When I play this with my classes in the future, I will make signs to hang around the necks of the eliminated participants so that it is easy to keep track of who is a ghost participant and who is a living participant.

ELIMINATION SIMPLIFICATION #10: Non-violence

We didn’t use a non-violent adaptation, but here are two ways that you could:

- Click here to read about Bad Unicorn from Erica Peplinski, an elementary Spanish teacher. She also provided Spanish resources for you to use!

- Set it up like the TV show “Survivor”. Instead of a town, everyone is a contestant on an island. The "Assassins" are just people in the group that are cheating in order to eliminate/get rid of other contestants, so they do things like steal people's food, send them floating off into the ocean, etc. The people that they target can no longer participate in the game and have to leave the island. There is a tribunal every day and the remaining participants try to figure out who the cheaters are and kick them off the island.

Takeaways from Simplified Elimination

After the game ended, we spent some time debriefing and discussing what we observed that made this game so effective and enthralling. Here are some of the things that we observed:

OBSERVATION #1: Gestures matter

Not only do gestures support comprehension, but they also allow you to communicate because they are body language. You can react with gestures even before you have the language to react verbally because we long to contribute. Often, I would gesture something that I wanted to say, and someone near me that knew the word would feed it to me, so then I would be able to gesture and say the word. Other times, Ben would see me and say what I wanted to, asking “Oh, she eats FIVE hamburgers?”, and then I would say “YES!”.

OBSERVATION #2: Word walls matter

We were in an empty room and had no means to write the words that we were learning on the wall, and we were all aching to see them. It would have been very helpful to have the words on the wall for Ben to point to as he said them! Always write your new words on the board, even if you don’t put the translation beside them (although that would be even better).

OBSERVATION #3: Remind students what they know

This isn’t an observation, but it was shared and I love it! Diane Neubauer, who created Mandarin resources for this game, created a list of expressions that the students can reference, consisting of things that they have already heard and been exposed to that they could blurt. She encourages them to use the language that they already have in order to engage in the game. Once they start to really play with those things, she said that it is so gratifying because you can really hear the emotion. In my original Mafia post, you can download some posters that contain relevant expressions in Spanish.

OBSERVATION #4: Create a connection

Dr. Krashen observed that playing Mafia—even this adaptation of the violent, original version—bonded the participants and made us feel closer together, because we were participating together in this imaginary world that Ben had created. Even beyond that, it connected us (the students) to Ben (our teacher). We relied on him for everything, and we hung on his every word. This observation was spot on! I feel like Ben is my best friend after playing the game! And goodness, what a wonderful thing connection is for our students.

I will surely be playing this game often, and I hope that as you take it and try it in your classes, that you will share your experiences, your adaptations, and your observations with others!!