Michele Whaley, a Russian teacher at West High School in Anchorage, invited me to her classroom in 2009 to observe a TPRS® lesson. I went in expecting to see a glorified version of Simon Says. What I saw bemused me, and it drove me to park myself in front of my TV for the next three days with training DVDs playing and a pencil and notebook in hand. I have spent the last six years seeking out further training in TPRS® (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling) and other Comprehension Based™ strategies, and I have discovered that when used correctly they are not only incredibly fun and engaging, but effective and explicit as well.

Teachers that use Comprehension Based™ methods are often criticized for sacrificing quality for quantity: critics claim that while their students may be able to understand and produce large amounts of language, the language is full of errors because of a lack of explicit grammar instruction and/or error correction. In a world of “How well you teach = How well they learn”, the assumption is that Comprehension Based™ teachers just aren’t teaching that well.

WHAT IS EXPLICIT INSTRUCTION

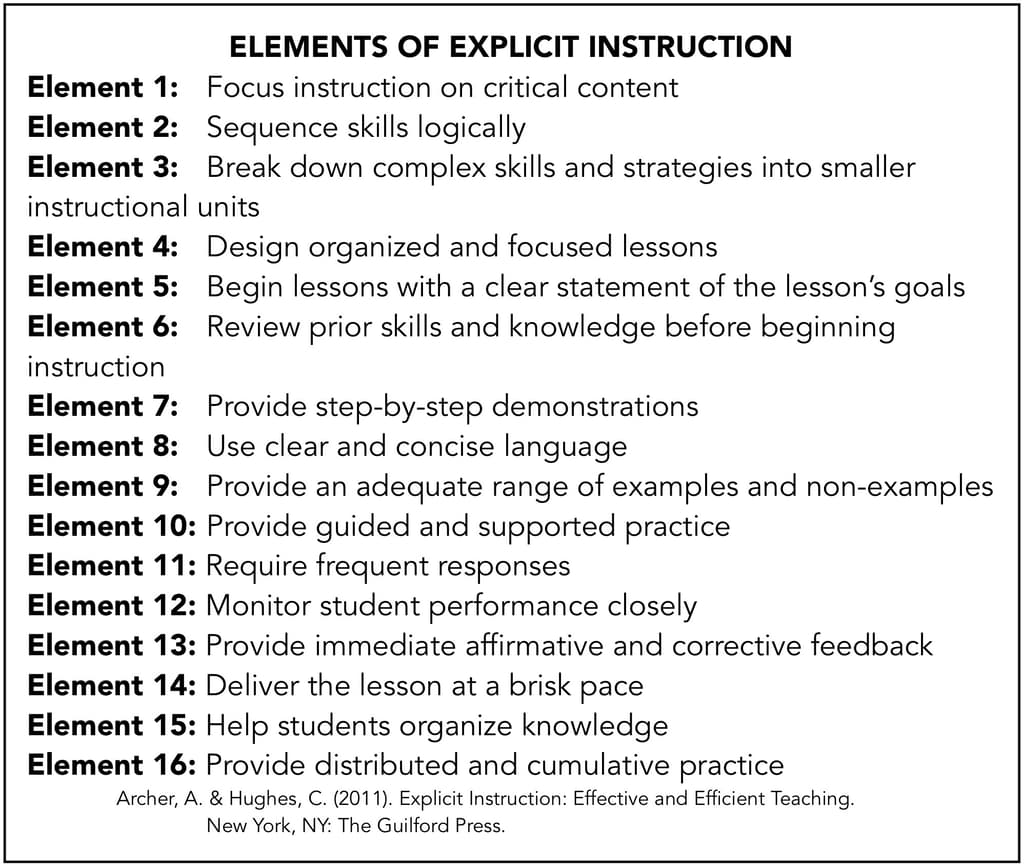

In Explicit Instruction: Effective and Efficient Teaching, Anita Archer and Charles Hughes have compiled the works of at least nine educational researchers and created a list of sixteen instructional behaviors that are characteristic of an explicit approach to teaching: an approach that is purported to promote achievement for all students because of its directness and scaffolding.

You might be surprised to learn that all sixteen elements that Archer and Hughes list are used by teachers that use Comprehension Based™ strategies of instruction. According to Archer and Hughes, Explicit Instruction is systematic, direct, engaging, and success oriented. In other words, students must be presented content in a step-by-step, logical order along with clear goals and explanations at each point along the way. The content must be presented in an interesting manner and with adequate supports so that all students achieve the goals with which they are presented.

Comprehension Based™ Teaching as Explicit Instruction

Trained Comprehension Based™ teachers provide their students with explicit, highly engaging grammar and vocabulary instruction through the use of several key features and strategies, all of which can be used to enhance any curriculum.

Comprehensible Input

According to Stephen Krashen’s input hypothesis, Comprehensible Input is the most important factor in language acquisition. The input hypothesis claims that we acquire language when we comprehend input (textual or auditory) that is one step above our current level of linguistic competency: in a nutshell; language can only be acquired when it is understood.

Comprehension Based™ teachers believe that everything that our students receive (hear or read) in class be comprehensible to them. In any subject area, teachers must use clear and concise language (Element 8) in order for their students to learn. It makes sense that this would be doubly true when language is both the means and the end of instruction, as is the case in language classrooms in which a minimum of 90 percent instructional time is spent in the target language. Cynthia Hitz, a long-time Spanish teacher from Pennsylvania, relates it to first language acquisition:

“When we talk to a young child, we don't have the option to switch to another language. We simply adjust our language to speak to the child in a manner that he understands. We naturally limit the vocabulary. The same applies to students learning their second language. I limit the vocabulary, which allows me to stay in the TL and to keep it comprehensible”.

Mike Peto, in “My generation of Polyglots” blogged about the importance of focusing instruction on input instead of output:

“You DO get out what you put in… you get OUTput if you put in comprehensible INput. What comes out (the writing) is profoundly shaped by what went in beforehand (all of the reading and listening that was comprehensible and interesting enough to grab the attention of the student)”.

Comprehension Based™ teachers include writing and speaking activities in their plans, but they are not the center of instruction: those skills will come as a natural overflow of the comprehensible language with which we flood them.

High Frequency Structures

While Comprehension Based™ strategies can be used to present any curriculum, many CI teachers strive to use curricula that are based on the systematic presentation of high frequency structures as opposed to the thematic units that are often found in traditional language textbooks. High frequency structures, which can be single words or phrases, are the terms that are most often used in a language. For example, structures like “has a problem”, “needs food”, and “wants something” are universal high frequency structures.

Carol Gaab, President of Fluency Matters, explains the importance of building curricula around high frequency structures:

“[The] real benefit of teaching high-frequency words first is that we (teachers) are equipping students with the most essential and useful words for communication. There are certain words that are used every day, words that are crucial to one's ability to communicate with a native speaker. Teaching these essential, non-negotiable parts of speech first has a direct positive impact on students' listening/reading comprehension and subsequently on their ability to respond (produce) in the Target Language”.

By teaching the most frequently occurring words in a language first, there is a logical sequence to the content (Elements 1 and 2) and a natural provision for distributed and cumulative practice (Element 16) of previous material. The teacher will continue to use these terms throughout the year, and students’ understanding of their meaning and usage is strengthened--not forgotten--as time passes.

CIRCLING

Circling is the most basic strategy in a Comprehension Based™ teacher’s repertoire. Circling allows a teacher to provide a high number of repetitions of the target structure in a systematic, engaging manner. To circle, a teacher begins by making a statement; for example, “Bob wants a puppy.” The teacher then asks questions about the statement by substituting variables for each component of the original statement (subject, verb, object). By asking different questions (yes/no, either/or, open-ended) and selecting variables that create funny or otherwise interesting statements, the teacher is constantly aware of his or her students’ understanding of the material, and the students remain engaged. Here is an example of a teacher script for circling: (The teacher pauses after each question and waits for the student(s) to respond before affirming the correct statement)

“Does Bob want a puppy?” “Yes, Bob wants a puppy!”

“Does Bob want a cat?” “No, Bob hates cats! They’re terrible! Bob wants a puppy!”

“Does Bob want a puppy or does Bob eat a puppy?” “Bob doesn’t eat a puppy! He’s not a monster! Bob wants a puppy.”

“What does Bob want?” “Bob wants a puppy.” “A cute little puppy!”

“Why does Bob want a puppy?” “Bob wants a puppy because girls like puppies and Bob wants a girlfriend!”

The constant stream of Q&A provides an adequate range of examples and non-examples, demands frequent responses from students, facilitates close monitoring of student performance, and naturally provides immediate and affirmative corrective feedback (Elements 9, 11-13). And, while it certainly keeps the lesson moving at a brisk pace (Element 14), teachers must be careful to not set a pace that is too brisk that students become lost in the flurry of questions.

Three Steps of TPRS®

Many teachers find TPRS®, a specific strategy for delivering Comprehensible Input, appealing because there are just three steps to remember: Establish Meaning, Asking the Story, Literacy. There are innumerable permutations of each step, but the steps remain the same. By following these three steps, teachers easily design organized and focused lessons (Element 4).

To establish meaning, teachers present the new structures to their students in the target language and give the meaning in English. Often, this is done by saying the word and translation and writing them on the board in two colors (for example, black for the target language and blue for English). By following this step, the teacher naturally begins lessons with a clear statement of the lesson’s goals (Element 5). Instruction then continues with the class created, teacher-directed story that includes the target structures. The process is complete after students have read a text that also includes the target structures; sometimes, it is a version of the class story, but other times it is unrelated.

Embedded Reading

Developed by Laurie Clarcq and Michele Whaley, Embedded Reading is one possibility for the “Literacy” step of TPRS. It is three or more readings in which each subsequent reading is an expanded version of the one that precedes it. Embedded Reading takes a text and breaks it down into smaller, more easily mastered pieces (Element 3). Laurie Clarcq explains how these readings meet the needs of all students in a class:

“The base reading is at the reading level of the lowest-achieving reader in the group. Each succeeding version contains the base reading and is designed to raise the skill level and the interest of the readers, without leaving any students behind. The activities designed to accompany the readings help to build these skills and challenge more advanced readers”. In this way, all students are both successful and appropriately challenged with each level of the reading.

Comprehension Checks

Comprehension Checks are strategic questions that allow the teacher to know whether or not students understand what they are being taught. Additionally, they allow students to affirm or correct understanding, make connections with previous concepts, and develop new knowledge. A trained Comprehension Based™ teacher uses comprehension checks constantly to assess language acquisition and to provide differentiated, guided, and supported practice (Element 10).

For example, a teacher could make the statement “Maria es una muchacha” (Maria is a girl). To one student, the teacher could ask “¿Quién es una muchacha?” (“Who is a girl?”). To another, “What does the word “muchacha” mean in English?” To yet another, the teacher could ask “How would you say “María is not a girl” or “María was a girl?”, thereby requiring the student to use a concept that was previously taught. The teacher matches the difficulty of the question to the ability of the student so that the student is challenged at his/her own level yet always able to be successful.

Pop-Up Grammar

Trained Comprehension Based™ teachers provide explicit grammar instruction through “Pop-up grammar” lessons: extremely short, contextualized explanations of grammatical concepts. In the experience of Terry Waltz, Ph.D., who provides specialized training in and for Mandarin Chinese:

“Pop-up grammar works [because] it is very, very highly contextualized. Putting things in context is important, [and] pop-up grammar easily wheels the grammar mini-lesson to where the context already exists.”

For example, after reading the sentence “Yo puedo bailar” (I can dance), a teacher might say “We have already seen the word ‘puede’ (‘s/he/it can’). This word is just a little different. The ‘-o’ on the end of “puedo” means that “I” is the subject, so this word means “I can”. Instead of teaching big grammar concepts like verb conjugation and agreement of gender and number with long notes and in grammatical terms, teachers present the concepts to their students by explicitly ‘noticing’ one small chunk at a time (Element 7). Then, they use circling, contrastive grammar, and comprehension checks to reinforce the concept. Waltz continues,

“...Pop-ups happen frequently. They take full advantage of the rich comprehensible input TPRS® provides, with many examples of different structures. Acquisition of words happens by matching language to meaning over and over; acquisition of patterns (grammar) happens by generalizing thousands of matches of language to meaning even when the word-level meaning is different”.

The frequency of pop-up grammar lessons ensure the distributed and cumulative practice of grammar concepts, just as the focus on high frequency structures does for vocabulary.

Contrastive Grammar

Contrastive grammar is a strategy that Comprehension Based™ teachers use to present grammatical concepts in context by comparing a new concept to one that students have already mastered. To begin instruction, the teacher reviews prior knowledge (Element 6) by writing the old term (a verb in the present tense, for example) on the board in two colors. Then, he or she establishes meaning for the new term (ex: the past tense of a verb) and adds it to the board. From there, the teacher uses circling and comprehension checks to compare and contrast the two terms so that students acquire the correct meaning and usage of the two terms. This strategy organizes students’ knowledge (Element 15) of the language without requiring the use of lengthy grammar notes.

Personalized Questions and Answers

The “heart” of Comprehension Based™ instruction is the teacher-student relationship. We strive to build this by making the students the center of instruction--both content and delivery. Personalized Question and Answer (PQA) sessions happen in almost every Comprehension Based™ classroom, every day. It is a time when the teacher asks questions that include the target structures to the students about their lives. For example, questions for the target structure “went” might be “Who went somewhere interesting last summer?” Then, their answers are discussed and expanded (and “embellished”, quite often) using techniques like circling, comprehension checks, and contrastive grammar. Kristy Placido, who teaches Spanish in Michigan, states:

“PQA allows learners to experience language structures in a different, more personal context. [It] allows modeling of first and second person language”.

She continues by saying that PQA makes a lesson compelling because people’ favorite topic of discussion is themselves!

By presenting students with compelling, highly useful content while meeting all elements of Explicit Instruction, it is easy to see why teachers across the globe are adding Comprehension Based™ strategies into their instructional toolbelt. If you’d like to see any of these strategies in action, please connect with a Comprehension Based™ Professional Learning Community in your area that you can observe. Just beware--you might find yourself the subject of the daily PQA!

-------------------------------

The previous article is an expanded version of something that I originally wrote to provide to my administrator as justification for using TPRS®/CI in my Spanish courses. As a Title I School on a Level 5 plan for improvement, all teachers were trained in Explicit Instruction and required to use instructional strategies characterized by its 16 elements. If you find yourself in a similar position, please email me directly at MartinaEBex at gmail dot com to request written permission to use this post as justification for TPRS®/CI.

All content © 2011-2018 The Comprehensible Classroom. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written consent from Martina Bex is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Martina Bex at The Comprehensible Classroom with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.